To Save the Church, Dismantle the Priesthood

A Former Catholic Priest Recommends the Faithful Renounce

the Power structure of the Institutional Church

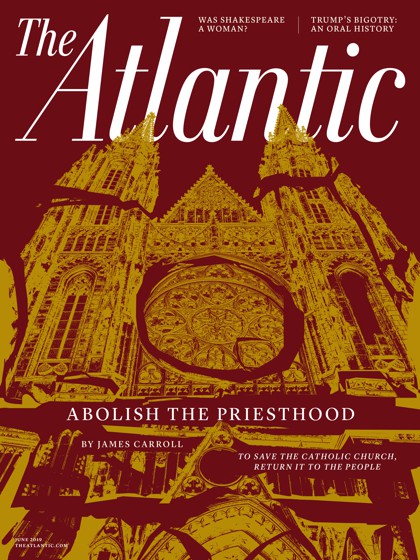

The cover story of the June 2019 Issue of The Atlantic

The conclusion of Divine Or Demoniac? – letting go of the institutional “leadership” and continuing spiritual practices without them – was also reached by James Carroll, author of this Atlantic article “To Save the Church, Dismantle the Priesthood.”

It seems that this might be an idea whose time has come.

What follows are excerpts from the article, which can be found in its entirety here. All emphasis added.

I

“Murder of the Soul”

Not long before The Boston Globe began publishing its series on predator priests, in 2002—the “Spotlight” series that became a movie of the same name—the government of Ireland established a commission, ultimately chaired by Judge Sean Ryan, to investigate accounts and rumors of child abuse in Ireland’s residential institutions for children, nearly all of which were run by the Catholic Church.

The Ryan Commission published its 2,600-page report in 2009. Despite government inspections and supervision, Catholic clergy had, across decades, violently tormented thousands of children. The report found that children held in orphanages and reformatory schools were treated no better than slaves—in some cases, sex slaves. Rape and molestation of boys were “endemic.” Other reports were issued about other institutions, including parish churches and schools, and homes for unwed mothers—the notorious “Magdalene Laundries,” where girls and women were condemned to lives of coercive servitude. The ignominy of these institutions was laid out in plays and documentary films, and in Philomena, the movie starring Judi Dench, which was based on a true story. The homes-for-women scandal climaxed in 2017, when a government report revealed that from 1925 to 1961, at the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home, in Tuam, County Galway, babies who died—nearly 800 of them—were routinely disposed of in mass graves or sewage pits. Not only priests had behaved despicably. So had nuns.

In August 2018, Pope Francis made a much publicized visit to Ireland. His timing could not have been worse. Just then, a second wave of the Catholic sex-abuse scandal was breaking. In Germany, a leaked bishops’ investigation revealed that from 1946 to 2014, 1,670 clergy had assaulted 3,677 children. Civil authorities in other nations were launching investigations, moving aggressively to preempt the Church. In the United States, also in 2018, a Pennsylvania grand jury alleged that over the course of 70 years, more than 1,000 children had been abused by more than 300 priests across the state. Church authorities had successfully silenced the victims, deflected law enforcement, and shielded the predators. The Pennsylvania report was widely taken to be a conclusive adjudication, but grand-jury findings are not verdicts. Still, this record of testimony and investigation was staggering. The charges told of a ring of pedophile priests who gave many of their young targets the gift of a gold cross to wear, so that the other predator priests could recognize an initiated child who would not resist an overture. “This is the murder of a soul,” said one victim who testified before the grand jury.

Attorneys general in at least 15 other states announced the opening of investigations into Church crimes, and the U.S. Department of Justice followed suit. Soon, in several states, teams of law-enforcement agents armed with search warrants burst into diocesan offices and secured records. The Texas Rangers raided the offices of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, which was presided over by Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. DiNardo had been presented by the Church as the new face of accountability and transparency when he came to Galveston-Houston in 2004. The rangers seized an archive of abuse—boxes of sex-allegation files along with computers, including DiNardo’s. The cardinal was accused of protecting a particularly egregious predator priest.

Read: The ‘Spotlight’ effect: This church scandal was revealed by outsiders

These and other investigations will produce an avalanche of scandal for years to come. As all of this was unfolding, Pope Francis responded with a meek call for a four-day meeting of senior bishops, to be held in Rome under the rubric “The Protection of Minors in the Church.” This was like putting Mafia chieftains in charge of a crime commission.

Before, during, and after his trip to Ireland, Francis had expressed, as he put it, “shame and sorrow.” But he showed no sign of understanding the need for the Church to significantly reform itself or to undertake acts of true penance.

One of the astonishments of Pope Francis’s Irish pilgrimage was his claim, made to reporters during his return trip to Rome, that until then he had known nothing of the Magdalene Laundries or their scandals: “I had never heard of these mothers—they call it the laundromat of women, where an unwed woman is pregnant and goes into these hospitals.” Never heard of these mothers? When I read that, I said to myself: A lie. Pope Francis is lying. He may not have been lying—he may merely have been ignorant. But to be uninformed about the long-simmering Magdalene scandal was just as bad. As I read the pope’s words, a taut wire in me snapped.

The wire had begun to stretch a quarter of a century ago, when I was starting out as a Boston Globe columnist. Twenty years earlier, I had been a Catholic priest, preoccupied with war, social justice, and religious reform—questions that defined my work for the Globe. One of my first columns, published in September 1992, was a reflection on the child-sex-abuse crimes of a Massachusetts priest named James Porter. I argued that Porter’s predation had been enabled by the Church’s broader culture of priest-protecting silence. Responding to earlier Globe stories about Porter, an infuriated Cardinal Bernard Law, the archbishop of Boston, had hurled an anathema that seemed to come from the Middle Ages: “We call down God’s power on the media, particularly the Globe.” It took a decade, but God’s power eventually came down on Law himself.

In tandem with the “Spotlight” series and afterward, more than a dozen of my columns on priestly sex abuse ran on the op-ed page, with titles such as “Priests’ Victims Victimized Twice” and “Meltdown in the Catholic Church.” I became a broken record on the subject.

Without making a conscious decision, I simply stopped going to Mass. I embarked on an unwilled version of the Catholic tradition of “fast and abstinence”—in this case, fasting from the Eucharist and abstaining from the overt practice of my faith. I am not deluding myself that this response of mine has significance for anyone else—Who cares? It’s about time!—but for me the moment is a life marker. I have not been to Mass in months. I carry an ocean of grief in my heart. [Very much like every devotee who has left ISKCON in disgust].

From October 1999: James Carroll on the Holocaust and the Catholic Church

Clericalism, with its cult of secrecy, its theological misogyny, and its hierarchical power, is at the root of Roman Catholic dysfunction. My five years in the priesthood, even in its most liberal wing, gave me a fetid taste of this caste system. Clericalism, with its cult of secrecy, its theological misogyny, its sexual repressiveness, and its hierarchical power based on threats of a doom-laden afterlife, is at the root of Roman Catholic dysfunction. The clerical system’s obsession with status thwarts even the merits of otherwise good priests and distorts the Gospels’ message of selfless love, which the Church was established to proclaim. Clericalism is both the underlying cause and the ongoing enabler of the present Catholic catastrophe. I left the priesthood 45 years ago, before knowing fully what had soured me, but clericalism was the reason.

Clericalism’s origins lie not in the Gospels but in the attitudes and organizational charts of the late Roman empire. Under Emperor Constantine, in the fourth century, Christianity effectively became the imperial religion and took on the trappings of the empire itself. A diocese was originally a Roman administrative unit. A basilica, a monumental hall where the emperor sat in majesty, became a place of worship. A diverse and decentralized group of churches was transformed into a quasi-imperial institution—centralized and hierarchical, with the bishop of Rome reigning as a monarch. Church councils defined a single set of beliefs as orthodox, and everything else as heresy.

When I became a priest, I placed my hands between the hands of the bishop ordaining me—a feudal gesture derived from the homage of a vassal to his lord. In my case, the bishop was Terence Cooke, the archbishop of New York. Following this rubric of the sacrament, I gave my loyalty to him, not to a set of principles or ideals, or even to the Church. [this is exactly the same thing that we find in today’s ISKCON: both guru and disciple make an oath to the GBC, leading to my conclusion that the GBC are refashion ISKCON into another Roman Church.]

Pope John XXIII’s successors were in clericalism’s grip, which is why the reforms of his council were short-circuited. John had, for instance, initiated a reconsideration of the Church’s condemnation of artificial contraception—a commission he established overwhelmingly voted to repeal the ban—but the possibility of that change was preemptively shut down by his successor, Pope Paul VI, mainly as a way of protecting papal authority. Now, with children as victims and witnesses both, the corruption of priestly dominance has been shown for the evil that it is. Clericalism explains both how the sexual-abuse crisis could happen and how it could be covered up for so long. If the structure of clericalism is not dismantled, the Roman Catholic Church will not survive, and will not deserve to.

IV

A Culture of Denial

Pope Francis, challenged by the disgrace of his close ally, the now-defrocked Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, of Washington; by accusations, like Viganò’s, of his own complicity in the cover-up of sexual abuse; and by the moral wreckage of the Church around the world, responded with silence, denial, and a business-as-usual summoning of crimson-robed men to Rome.

Events in subsequent months only magnified the scale of the Church’s failure. With maddening equilibrium, Pope Francis acknowledged, in response to a reporter’s question early this year, that the rape of nuns by priests and bishops remains a mostly unaddressed Catholic problem. In Africa, once AIDS became common, priests began coercing nuns into becoming sexual servants, because, as virgins, they would likely not carry the HIV virus. It was reportedly common for such priests to sponsor abortions when the nuns became pregnant. “It’s true,” Francis said calmly. “There are priests and bishops who have done that.” Nuns have come forward in India to charge priests with rape. In April, a bishop was charged with the rape and illegal confinement of a nun, whom he allegedly assaulted regularly over two years, in the southern state of Kerala. (The bishop has denied the charges.) The nun said she reported the bishop to the police only after appealing to Church authorities repeatedly—and being ignored.

A signal of what to expect from the meeting of bishops in Rome came in February from Francis himself, who, on the eve of the gathering, turned on those he called “accusers.” He said, with pointed outrage, “Those who spend their lives accusing, accusing, and accusing are … the friends, cousins, and relatives of the devil.” His spray-shot diatribe seemed aimed as much at victims seeking justice as at the right-wing critics who have clearly gotten to him. At the meeting, the bishops dutifully employed watchwords such as transparency and repentance, yet they established no new structures of prevention and accountability. An edict promulgated in March makes reporting allegations of abuse mandatory, but it applies only to officials of the Vatican city-state and its diplomats, and the reporting is not to civil authorities but to other Vatican officials. Francis proclaimed “an all-out battle” against priestly abuse and said the Church must protect children “from ravenous wolves.” But he said nothing about who breeds such wolves or who sets them loose. Worse, he deflected the specifically Catholic nature of this horror by noting that child abuse and sexual malfeasance happen everywhere, as if the crimes of Catholic clergy are not so bad. Coming like a punctuation mark the day after the Vatican gathering adjourned was a full report from Australia on the matter of Cardinal George Pell. Formerly the head of Vatican finances and one of Francis’s closest advisers, Pell had been found guilty of sexually violating two altar boys in a sacristy right after presiding at the Eucharist.

In the Americas and Africa; in Europe, Asia, and Australia—wherever there were Catholic priests, there were children being preyed upon and tossed aside. Were it not for crusading journalists and lawyers, the sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests would still be hidden, and rampant. A power structure that is accountable only to itself will always end up abusing the powerless. According to one victim, Cardinal Law, of Boston, before being forced to resign because of his support for predator priests, attempted to silence the man by invoking the sacred seal: “I bind you by the power of the confessional,” Law said, his hands pressing on the man’s head, “not to speak to anyone else about this.”

Read: Catholics are desperate for tangible reforms on clergy sex abuse

While a relatively small number of priests are pedophiles, it is by now clear that a far larger number have looked the other way. In part, that may be because many priests have themselves found it impossible to keep their vows of celibacy, whether intermittently or consistently. Such men are profoundly compromised. Gay or straight, many sexually active priests uphold a structure of secret unfaithfulness, a conspiracy of imperfection that inevitably undercuts their moral grit. At a deeper level, Catholic clerics may be reluctant to judge their predatory fellows, because a priest, even if he is a person of full integrity, is always vulnerable to a feeling of having fallen short of an impossible ideal: to be “another Christ.” Where in such a system is there room for being human? I remember retreat masters citing scripture to exhort us priests during our seminary days “to be perfect, even as your heavenly Father is perfect.” Moral perfection, we were told, was a vocational mandate. That such hubristic claptrap came from blatantly imperfect men did nothing to lighten the load of the admonition. I know from my own experience how priests are primed to feel secretly unworthy. Whatever its cause, a guilt-ridden clerical subculture of moral deficiency has made all priests party to a quiet dissembling about the deep disorder of their own condition. That subculture has licensed, protected, and enabled those malevolent men of the cloth who are prepared to exploit the young.

V

“There I Am”

Pope Francis expresses “shame and sorrow” over the sexual abuse of children by priests, yet he instinctively defends perpetrators against their accusers. He has called clericalism “a perversion of the Church.” But what does he actually mean by that? He denounces the clerical culture in which abuse has found its niche but does nothing to dismantle it. In his responses, he embodies that culture. I was never surprised when his papal predecessors behaved this way—when, for instance, Cardinal Ratzinger, before becoming Pope Benedict XVI, prohibited bishops from referring cases of predator priests to civil authorities, binding them under what he called the “pontifical secret.” Even now, as a supposedly sidelined pope emeritus, Ratzinger is still defending the old order. In April he published, in a Bavarian periodical, a diatribe that was extraordinary as much for its vanity as for its ignorance. Benedict blamed sex abuse by priests on the moral laxity of the 1960s, the godlessness of contemporary culture, the existence of homosexual cliques in seminaries—and the way his own writings have been ignored. His complaint offered a barely veiled rebuttal to the pontificate of his successor, and is sure to reenergize the present pope’s right-wing critics. But alas, the pope emeritus and his allies may not have real cause for worry. That an otherwise revolutionary pope like Francis demonstrates personally the indestructibility of clericalism is the revelation.

But Catholic clericalism is ultimately doomed, no matter how relentlessly the reactionaries attempt to reinforce it. The Vatican, with its proconsul-like episcopate, is the pinnacle of a structure of governance that owes more to emperors than to apostles. The profound discrediting of that episcopate is now under way. In North America and Europe, the falloff of Catholic laypeople from the normal practice of the faith has been dramatic in recent years, a phenomenon reflected in the diminishing ranks of clergy: Many parishes lack any priests at all. In the United States, Catholicism is losing members faster than any other religious denomination. For every non-Catholic adult who joins the Church through conversion, there are six Catholics who lapse.

The power structure is not the Church. The Church is the people of God. What if multitudes of the faithful, appalled by what the sex-abuse crisis has shown the Church leadership to have become, were to detach themselves from—and renounce—the cassock-ridden power structure of the Church and reclaim Vatican II’s insistence that that power structure is not the Church? The Church is the people of God. The Church is a community that transcends space and time.

Catholics should not yield to clerical despots the final authority over our personal relationship to the Church.

I propose a kind of internal exile. One imagines the inmates of internal exile as figures in the back of a church, where, in fact, some dissenting priests and many free-spirited nuns can be found as well. Think of us as the Church’s conscientious objectors. We are not deserters. The exiles themselves will become the core, as exiles were at the time of Jesus. This is already happening, in front of our eyes.

In what way, one might ask, can such institutional detachment square with actual Catholic identity? Through devotions and prayers and rituals that perpetuate the Catholic tradition in diverse forms, undertaken by a wide range of commonsensical believers, all insisting on the Catholic character of what they are doing. Their ranks would include ad hoc organizers of priestless parishes; parents who band together for the sake of the religious instruction of youngsters; social activists who take on injustice in the name of Jesus; and even social-media wizards launching, say, #ChurchResist. As ever, the Church’s principal organizing event will be the communal experience of the Mass, the structure of which—reading the Word, breaking the bread—will remain universal; it will not need to be celebrated by a member of some sacerdotal caste. The gradual ascendance of lay leaders in the Church is in any case becoming a fact of life, driven by shortages of personnel and expertise. Now is the time to make this ascendance intentional, and to accelerate it. The pillars of Catholicism—gatherings around the book and the bread; traditional prayers and songs; retreats centered on the wisdom of the saints; an understanding of life as a form of discipleship—will be unshaken.

The Vatican itself may take steps, belatedly, to catch up to where the Church goes without it. Fine. But in ways that cannot be predicted, have no central direction, and will unfold slowly over time. The exiles themselves will become the core, as exiles were the core at the time of Jesus. They will take on responsibility and ownership—and, as responsibility and ownership devolve into smaller units, the focus will shift from the earthbound institution to its transcendent meaning. This is already happening, in front of our eyes. Tens of millions of moral decisions and personal actions are being informed by the choice to be Catholics on our own terms, untethered from a rotted ancient scaffolding. The choice comes with no asterisk. We will be Catholics, full stop. We do not need anyone’s permission. Our “fasting and abstaining” from officially ordered practice will go on for as long as the Church’s rebirth requires, whether we live to see it finished or not. As anticlerical Catholics, we will simply refuse to accept that the business-as-usual attitudes of most priests and bishops should extend to us, as the walls of their temple collapse around them. What remains of the connection to Jesus once the organizational apparatus disappears? That is what I asked myself in the summer before I resigned from the priesthood all those years ago—a summer spent at a Benedictine monastery on a hill between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. I came to realize that the question answers itself. The Church, whatever else it may be, is not the organizational apparatus. It is a community of memory, keeping alive the story of Jesus Christ. The Church is an in-the-flesh connection to him—or it is nothing. The Church is the fellowship of those who follow him, of those who seek to imitate him—a fellowship, to repeat the earliest words ever used about us, of “those that loved him at the first and did not let go of their affection for him.”

Recent Comments